Image credit: G. Reddy

Image credit: G. Reddy

Abstract

A variety of neurodegenerative diseases are associated with amyloid plaques, which begin as soluble protein oligomers but develop into amyloid fibrils. Our incomplete understanding of this process underscores the need to decipher the principles governing protein aggregation. Mechanisms of in vivo amyloid formation involve a number of coconspirators and complex interactions with membranes. Nevertheless, understanding the biophysical basis of simpler in vitro amyloid formation is considered important for discovering ligands that preferentially bind regions harboring amyloidogenic tendencies. The determination of the fibril structure of many peptides has set the stage for probing the dynamics of oligomer formation and amyloid growth through computer simulations. Most experimental and simulation studies, however, have been interpreted largely from the perspective of proteins : the role of solvent has been relatively overlooked in oligomer formation and assembly to protofilaments and amyloid fibrils.

In this Account, we provide a perspective on how interactions with water affect folding landscapes of amyloid beta (Aβ) monomers, oligomer formation in the Aβ16–22 fragment, and protofilament formation in a peptide from yeast prion Sup35. Explicit molecular dynamics simulations illustrate how water controls the self-assembly of higher order structures, providing a structural basis for understanding the kinetics of oligomer and fibril growth. Simulations show that monomers of Aβ peptides sample a number of compact conformations. The formation of aggregation-prone structures (N*) with a salt bridge, strikingly similar to the structure in the fibril, requires overcoming a high desolvation barrier. In general, sequences for which N* structures are not significantly populated are unlikely to aggregate.

Oligomers and fibrils generally form in two steps. First, water is expelled from the region between peptides rich in hydrophobic residues (for example, Aβ16–22), resulting in disordered oligomers. Then the peptides align along a preferred axis to form ordered structures with anti-parallel β-strand arrangement. The rate-limiting step in the ordered assembly is the rearrangement of the peptides within a confining volume.

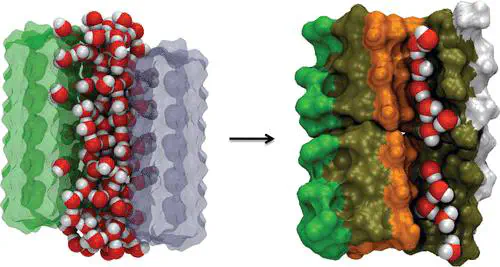

The mechanism of protofilament formation in a polar peptide fragment from the yeast prion, in which the two sheets are packed against each other and create a dry interface, illustrates that water dramatically slows self-assembly. As the sheets approach each other, two perfectly ordered one-dimensional water wires form. They are stabilized by hydrogen bonds to the amide groups of the polar side chains, resulting in the formation of long-lived metastable structures. Release of trapped water from the pore creates a helically twisted protofilament with a dry interface. Similarly, the driving force for addition of a solvated monomer to a preformed fibril is water release; the entropy gain and favorable interpeptide hydrogen bond formation compensate for entropy loss in the peptides.

We conclude by offering evidence that a two-step model, similar to that postulated for protein crystallization, must also hold for higher order amyloid structure formation starting from N*. Distinct water-laden polymorphic structures result from multiple N* structures. Water plays multifarious roles in all of these protein aggregations. In predominantly hydrophobic sequences, water accelerates fibril formation. In contrast, water-stabilized metastable intermediates dramatically slow fibril growth rates in hydrophilic sequences.